Honest Space

R - What does comfort mean in the context of space?

P.M – For me, comfort is rarely physical. It’s about resonance, whether a space aligns with the way I want to live. My background in craftsmanship makes me value practicality and clarity, but comfort goes beyond function.

A space is comfortable when it stands quietly for itself, when it doesn’t try to perform or persuade. If that resonance is missing, even the warmest materials feel wrong. The quieter a space is, the more honest it becomes, and that honesty is the real comfort.

P.M – For me, comfort is rarely physical. It’s about resonance, whether a space aligns with the way I want to live. My background in craftsmanship makes me value practicality and clarity, but comfort goes beyond function.

A space is comfortable when it stands quietly for itself, when it doesn’t try to perform or persuade. If that resonance is missing, even the warmest materials feel wrong. The quieter a space is, the more honest it becomes, and that honesty is the real comfort.

"These are not obstacles; they are generators of architecture"

R - When you begin a project, where do you start?

P.M - We never start with form. We start with the problem: the program, the site, the constraints, the cultural context. These are not obstacles; they are generators of architecture. Once the conditions are clear, we look closely at what already exists. It’s a very Swiss approach: begin with reality, not with an image. Architecture becomes stronger when it grows out of what is present. You take something given and refine it until it feels necessary.

P.M - We never start with form. We start with the problem: the program, the site, the constraints, the cultural context. These are not obstacles; they are generators of architecture. Once the conditions are clear, we look closely at what already exists. It’s a very Swiss approach: begin with reality, not with an image. Architecture becomes stronger when it grows out of what is present. You take something given and refine it until it feels necessary.

R - Is there a structure or detail from your childhood that still shapes how you build today?

P.M - Yes. Between 7th and 9th grade, during school holidays, I worked in my father’s sawmill. Stacking and drying wood created these simple six-meter-high structures: purely functional task, yet strangely sculptural in the way light moved through them and the presents they have. And always the smell of freshly cut wood. It taught me that necessity can create its own form of beauty.

Later, training as a furniture maker became the foundation of everything I do. Craft is not nostalgia, it’s a way of thinking. How something is made determines how it appears and how it lives over time.

P.M - Yes. Between 7th and 9th grade, during school holidays, I worked in my father’s sawmill. Stacking and drying wood created these simple six-meter-high structures: purely functional task, yet strangely sculptural in the way light moved through them and the presents they have. And always the smell of freshly cut wood. It taught me that necessity can create its own form of beauty.

Later, training as a furniture maker became the foundation of everything I do. Craft is not nostalgia, it’s a way of thinking. How something is made determines how it appears and how it lives over time.

"The goal isn’t perfection. It’s clarity with personality"

R - How do you know when a design is finished?

P.M - Unromantically, the timeline and the budget often decide it first. But architecturally, a project is finished when its logic becomes clear, when simplicity and pragmatism reach a point of inevitability, with a small twist that makes it ours.

When removing even one more element would weaken the whole, it’s done.

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s clarity with personality.

P.M - Unromantically, the timeline and the budget often decide it first. But architecturally, a project is finished when its logic becomes clear, when simplicity and pragmatism reach a point of inevitability, with a small twist that makes it ours.

When removing even one more element would weaken the whole, it’s done.

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s clarity with personality.

R - Can restraint be expressive?

P.M - Absolutely. Restraint is not the opposite of expression, often it’s the condition for it.

When you limit the number of gestures, the ones you keep gain strength. Materials, textures, and construction speak with more intensity.

We’re not interested in minimalism for its own sake. Reduction alone is not the aim.

The goal is to amplify presence, to make the ordinary feel unexpected, even extraordinary.

Restraint sharpens that presence. It makes the work more precise, more confident, more direct.

P.M - Absolutely. Restraint is not the opposite of expression, often it’s the condition for it.

When you limit the number of gestures, the ones you keep gain strength. Materials, textures, and construction speak with more intensity.

We’re not interested in minimalism for its own sake. Reduction alone is not the aim.

The goal is to amplify presence, to make the ordinary feel unexpected, even extraordinary.

Restraint sharpens that presence. It makes the work more precise, more confident, more direct.

"So rather than designing against aging, we design for it"

R - Do you consider your buildings to age? And if so, how do you design for that passage of time?

P.M - Aging is part of architecture, but our practice is still young, so we haven’t experienced it across decades.

For now, we design spaces that accept traces, slightly rough, forgiving environments that welcome life instead of resisting it.

If a child draws on the wall or colour hits the floor, it becomes part of the narrative, not a flaw.

So rather than designing against aging, we design for it: letting the building absorb time, and allowing those traces to become part of its character.

P.M - Aging is part of architecture, but our practice is still young, so we haven’t experienced it across decades.

For now, we design spaces that accept traces, slightly rough, forgiving environments that welcome life instead of resisting it.

If a child draws on the wall or colour hits the floor, it becomes part of the narrative, not a flaw.

So rather than designing against aging, we design for it: letting the building absorb time, and allowing those traces to become part of its character.

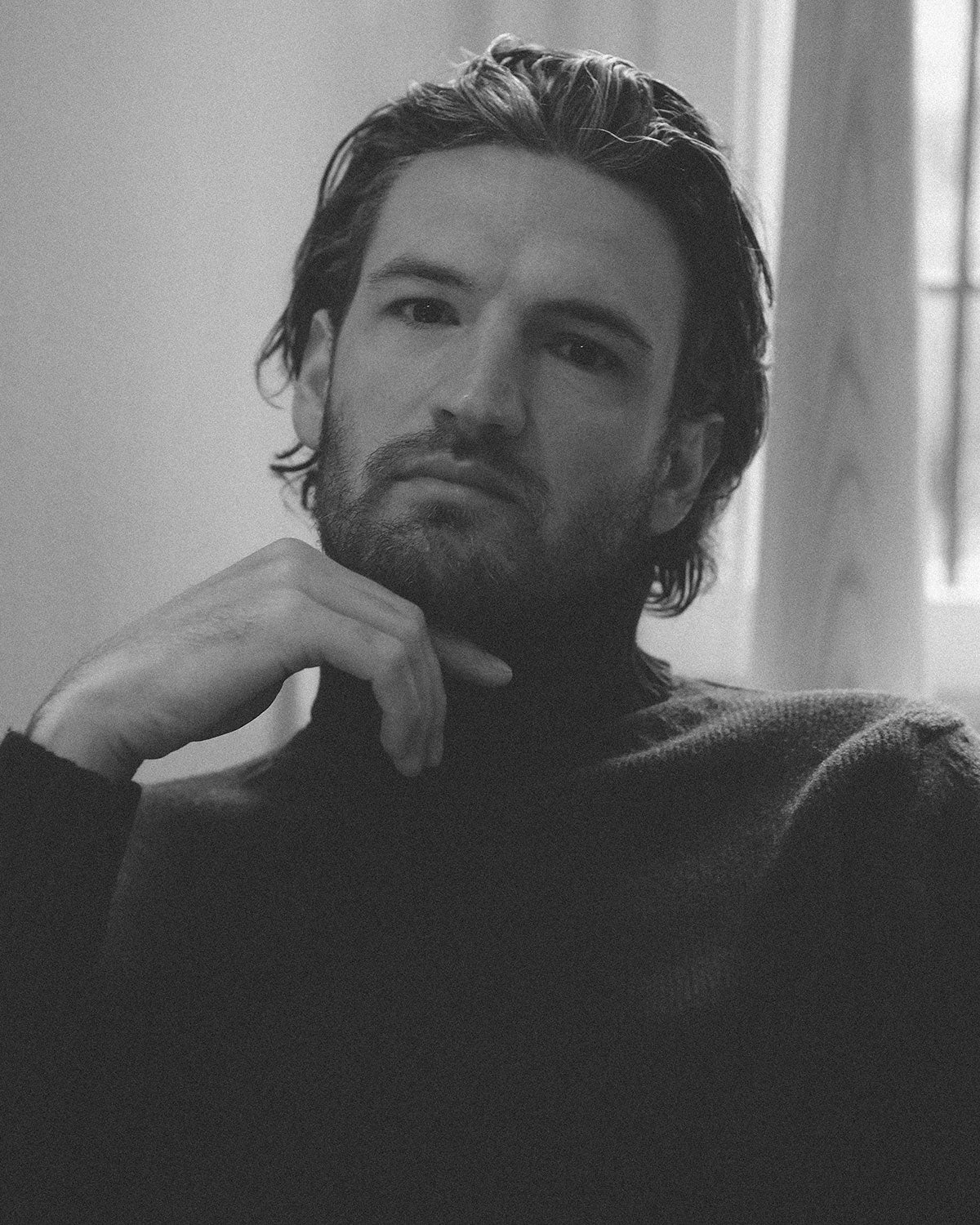

Patrick Müller is an architect and the co-founder of Ductus Studio based in Sweden and Switzerland. See what Patrick is wearing below: